This is a follow up post to another one where I discuss the probability of getting 3 groups of equal sizes when splitting a total of 90 subjects. In that post, we find that the probability of getting three groups with 30 subjects each is \(0.0091\)

I wanted to understand how this probability changes as we increase the number of equally sized groups to generate from a given sample of subjects, i.e. I want to see if the probability increases/decreases from 1-4 below:

- The probability of creating 2 groups of 45 subjects each

- The probability of creating 3 groups of 30 subjects each

- The probability of creating 5 groups of 18 subjects each

- The probability of creating 6 groups of 15 subjects each

Intuitively, the probability should go down as the number of equally sized groups goes up. Let’s verify this empirically. Let’s say we have \(N\) subjects and \(k\) groups of equal sizes to create. Generalizing the proof from the previous post, the process to create equally sized groups would be:

- Get the size of each group. Let

\(n = N/k\). This assumes\(N\)is divisible by\(k\). - Group 1: choose

\(n\)from the pool of\(N\)subjects. This can be done in\(\binom{N}{n}\)ways.\(N-n\)subjects now remain. - Group 2: choose

\(n\)from the remaining pool of\(N-n\)subjects. This can be done in\(\binom{N-n}{n}\)ways.\(N-2n\)subjects now remain. - Group 3: choose

\(n\)from the remaining pool of\(N-2n\)subjects. This can be done in\(\binom{N-2n}{n}\)ways.\(N-3n\)subjects now remain. - Repeat the process till only

\(n\)subjects remain, this is group\(k\).

The number of ways to create \(k\) groups of equal size \(n\) is given by:

\begin{align} & \binom{N}{n} \times \binom{N-n}{n} \times \binom{N-2n}{n} \dots \binom{3n}{n} \times \binom{2n}{n} \\ & = \frac{N!}{(N-n)!n!} \times \frac{(N-n)!}{(N-2n)!n!} \times \frac{(N-2n)!}{(N-3n)!n!} \dots \frac{3n!}{2n!n!} \times \frac{2n!}{n!n!} \\ & = \underbrace{\frac{N!}{(N-n)!n!} \times \frac{(N-n)!}{(N-2n)!n!} \times \frac{(N-2n)!}{(N-3n)!n!} \dots \frac{3n!}{2n!n!} \times \frac{2n!}{n!n!}}_{k-1\text{ terms}} \\ & = \frac{N!}{{(n!)}^k} \tag{1} \end{align}

Similary, we can extend the reasoning in the previous post to get the total number of ways of creating \(k\) groups from \(N\) subjects to be:

\begin{align} \underbrace{k \times k \times k \dots k}_{N\text{ terms}} = k^N \tag{2} \end{align}

(1) and (2) give us the value for the probability:

\begin{align} P(\text{k groups of equal sizes}) = \frac{N!}{{(n!)}^k k^N}, \,\,\, \text{where} \,\,\, n = N/k \end{align}

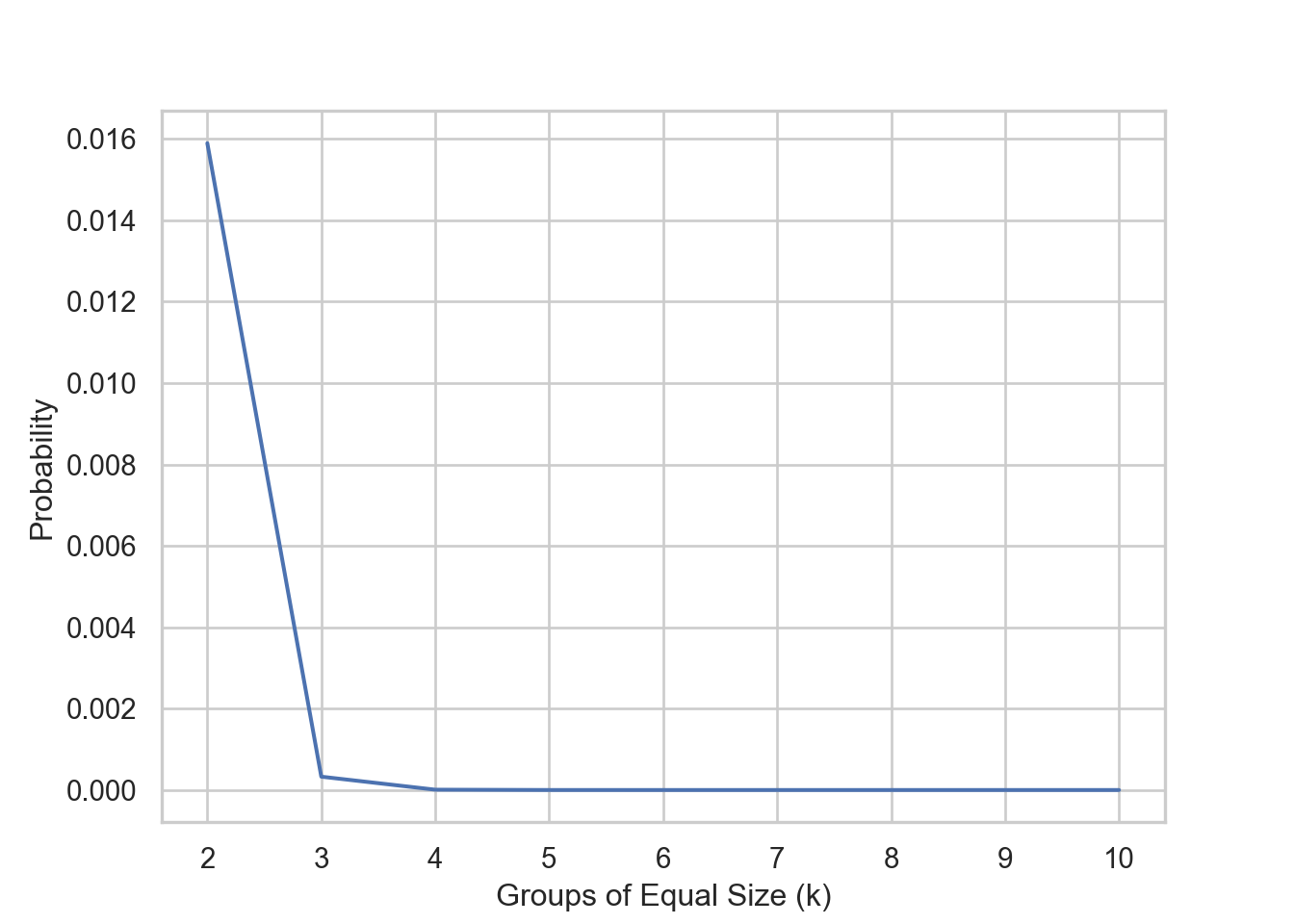

This formulation indicates that my intuition from earlier was accurate. I expect the probability to decrease as \(k\) (the number of equally sized groups to create) increases. Let’s visualize this. I set \(N = 2520\) and vary \(k\) from \(2 \dots 10\) (\(2520\) is the least common multiple of the numbers \(2 \dots 10\). This is to satisfy the divisibility assumption).

from math import factorial

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

N = 2520

k_range = range(2, 11)

def prob_equal(N, k):

n = N//k

return factorial(N)/(((factorial(n))**k) * k**N)

prob = [prob_equal(N, k) for k in k_range]

# plot

sns.set_theme(style="whitegrid")

sns.lineplot(x=k_range, y=prob)

# label the axes

plt.xlabel("Groups of Equal Size (k)")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.show()

The probability decreases as expected, also notice the steep decline as we go from \(k=2\) to \(k=3\). All this to say, given a pool of subjects \(N\), its increasingly unlikely to create \(k\) groups of equal sizes as \(k\) increases.